For awards, reviews, excerpts and other information please scroll down.

Publisher: Toronto: Stoddart Publishing, 1994.

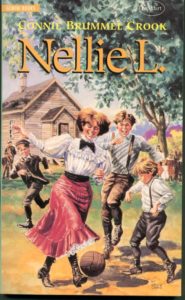

Cover Art: David Craig

Summary: Who was Nellie L.? None other than Nellie Mooney – later Nellie McClung – a Manitoba farm girl who became Canadas’s most famous pioneer for women’s rights. In this book, meet Nellie L. at the age of ten, plotting to run a race with the boys – absolutely unheard of in Canada in the 1880’s. Then follow her fight to overcome the criticism of her mother and the prejudices of society to help Canadian women.

AWARDS

Geoffrey Bilson Historical Fiction Award shortlist, 1995

Canadian Children’s Book Centre Our Choice selection, 1995/6

REVIEWS

Nellie L. is a highly accessible source of information about the formative years of an important Canadian suffragette, reformer, legislator, and author. . . . Author Constance Crook effectively weaves information about the Riel Rebellion, women’s suffrage, the beginning of the temperance movement, health care, and domestic concerns into her account of the day-to-day life of the large, loving Mooney family.

Consideration of school assignments aside, Nellie L. will also appeal to readers who have enjoyed such period classics as Carol R. Brink’s Caddie Woodlawn and L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables.

— Quill & Quire

Nellie brought to life

. . . Nellie comes across not as a saint, but as an interesting person. She fights with her brother, resents her mother’s strict discipline and loves her father’s Irish humor. Without a chance to attend school until she is 10, she quickly makes up for lost time.

In short, she is a heroine with whom many girls will identify, and whom even boys may admire.

This is a lively, enjoyable book that manages also to impart a good deal of little known information about one of Manitoba’s best-known historical figures.

—Winnipeg Free Press

EXCERPTS

Nellie L.

Part One: Prairie Girl

Part Two: School Days

Part Three: Nellie’s Vision

Chapter Six

Nellie woke up with an overwhelming feeling of dread. The worst had come. It was October 15, 1883, the first day of school. She put her wrist to her forehead, hoping to feel a fever. No luck. “Well,” she thought, “there’s nothing for it but to face the thing squarely. Sooner or later, the world will have to find out that I don’t even know how to read.”

Her mother’s words to Mrs. Ingram rang in Nellie’s ears. “Nellie’s a big girl – almost ten – and she won’t learn anything!” She buried her head in the big feather pillow and tried to drown out the memory.

Nellie tries to pretend that she is sick like her sister Hannah and cannot go to school but doesn’t get away with it.

At school, each pupil is called up separately to show the teacher how much she/he is able to read and count. When she reaches the teacher’s desk, Nellie blurts out the following:

“I can’t read. Hannah tried to teach me, but I can’t even learn. And this Saturday, I’ll be ten.”

“That’s a good age to start school,” said Mr. Schultz, “and you’ll be reading before Christmas break.”

Nellie stared back at him. He hadn’t scolded her for being ignorant. But how could he be so sure she would be able to read before Christmas? All the same, there was something about the way he said it that made Nellie believe him. He looked steadily at her with his grey-green eyes. “You’ll see,” he said, and smiled kindly.

Nellie floated back to her seat. Her terrible burden had been lifted. She didn’t care if Abigail had ten hundred different slate frames to match all her different store-bought dresses. And she didn’t notice the neat sums that Bob had prepared as he slid out of his seat. All she knew was that she would be able to read by Christmas.

Times were hard for Nellie’s parents and most pioneers to western Canada in those days. Nellie and her sister Hannah often carried fresh well-water and sandwiches to the men who worked hard in the fields. Opinions of that day clearly affected the forming of her attitudes and character.

Father smiled back at Frank and picked off a head of wheat. “Sure, and it is a grand country that can grow forty bushels of this to the acre,” he said. “It’s great to be alive on a day like this, with enough to eat and a bed to lie on.”

“That’s as may be,” said Nathan Smith with a deep frown, “but life ain’t always easy out here.” His deep-set eyes and bushy eyebrows looked darker than usual. Nellie leaned forward a bit to hear what he was going to say.

Everyone nodded sympathetically. Nathan Smith had just lost his wife. He brushed back a tear with the back of his dust-covered hand.

“Poor Sarah was still in her prime when she just up and died, and me with all the fall work upon me. It wasn’t like her to just quit.”

“No, that’s true. But I guess there’s one good thing,” George Ingram said. “She wasn’t sick for long.”

“No, she wasn’t. She never cost me a doctor’s bill.”

“Sarah was a good woman,” Father said.

“That she was, that she was. She was as strong as any horse I have on the place. And often when I’d be up in bed, I’d hear her downstairs poundin’ out loaves of bread. When I got up in the mornin’, she’d have it all baked, waitin’ for me. She was a great wife!”

Nellie stared at the wheat stubble on the ground, wondering when Mrs. Smith had had the time to sleep. She knew many farmers’; wives died young, and she started to feel angry at the farmers who treated their wives like plough horses.